2019

loop

in collaboration with Joao Villas, JP Garcia, Diego Rios, Gaby Hartel, Alex Gezhey, Nora Hartel, Clara Verdier, Margo van Rooyen, Adam Relihan, Emmie Ray, Qiang Li, John Atherton, Dafni Athanasopoulou, Eleni Athanasopoulou

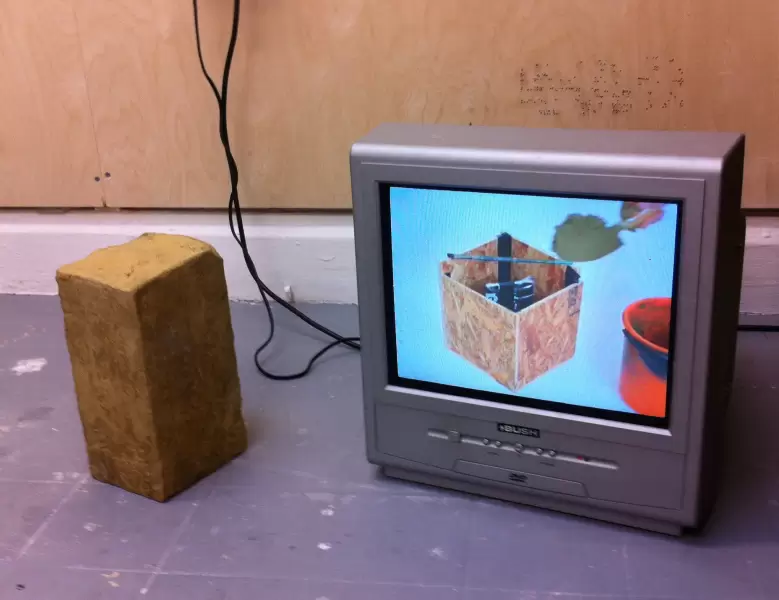

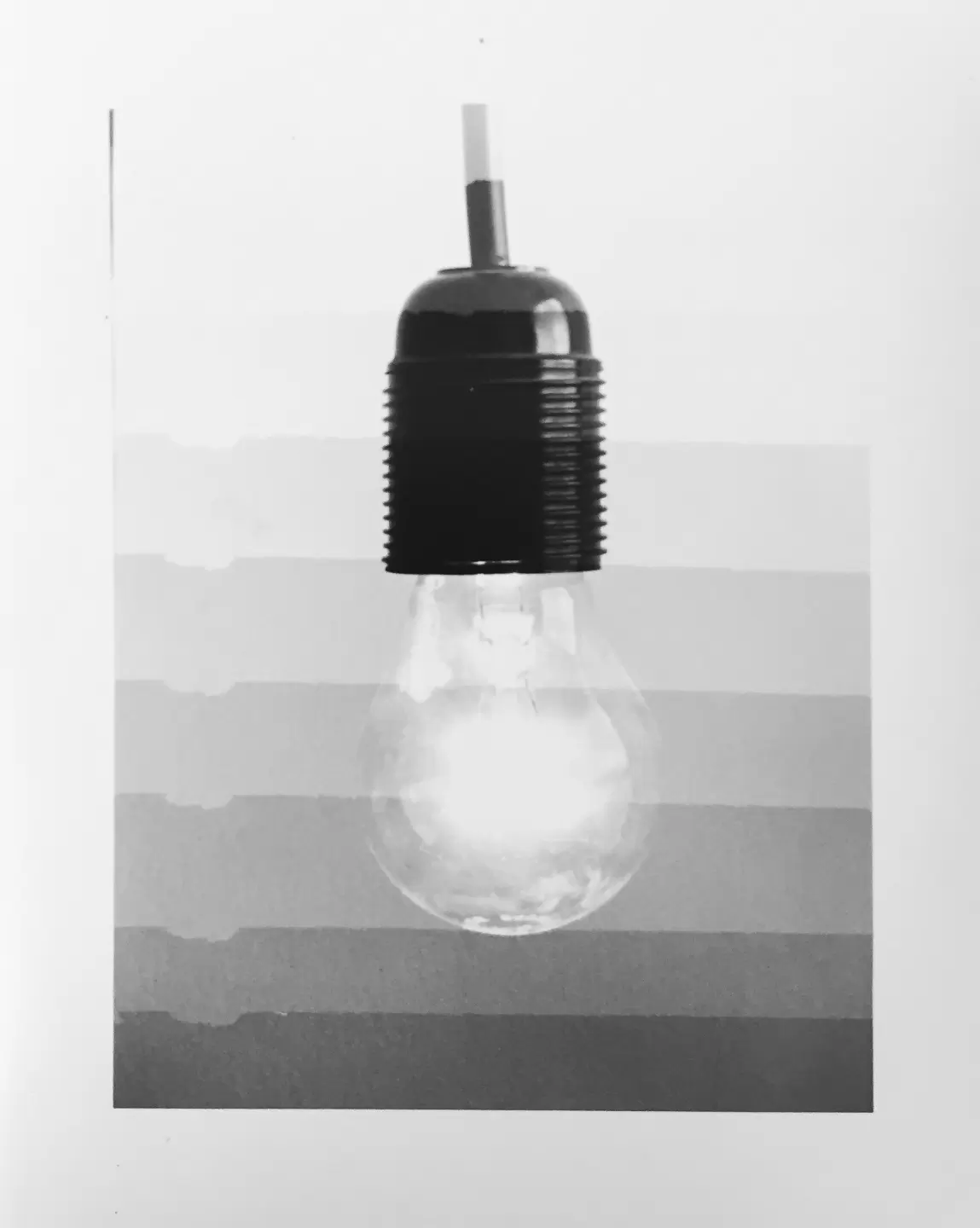

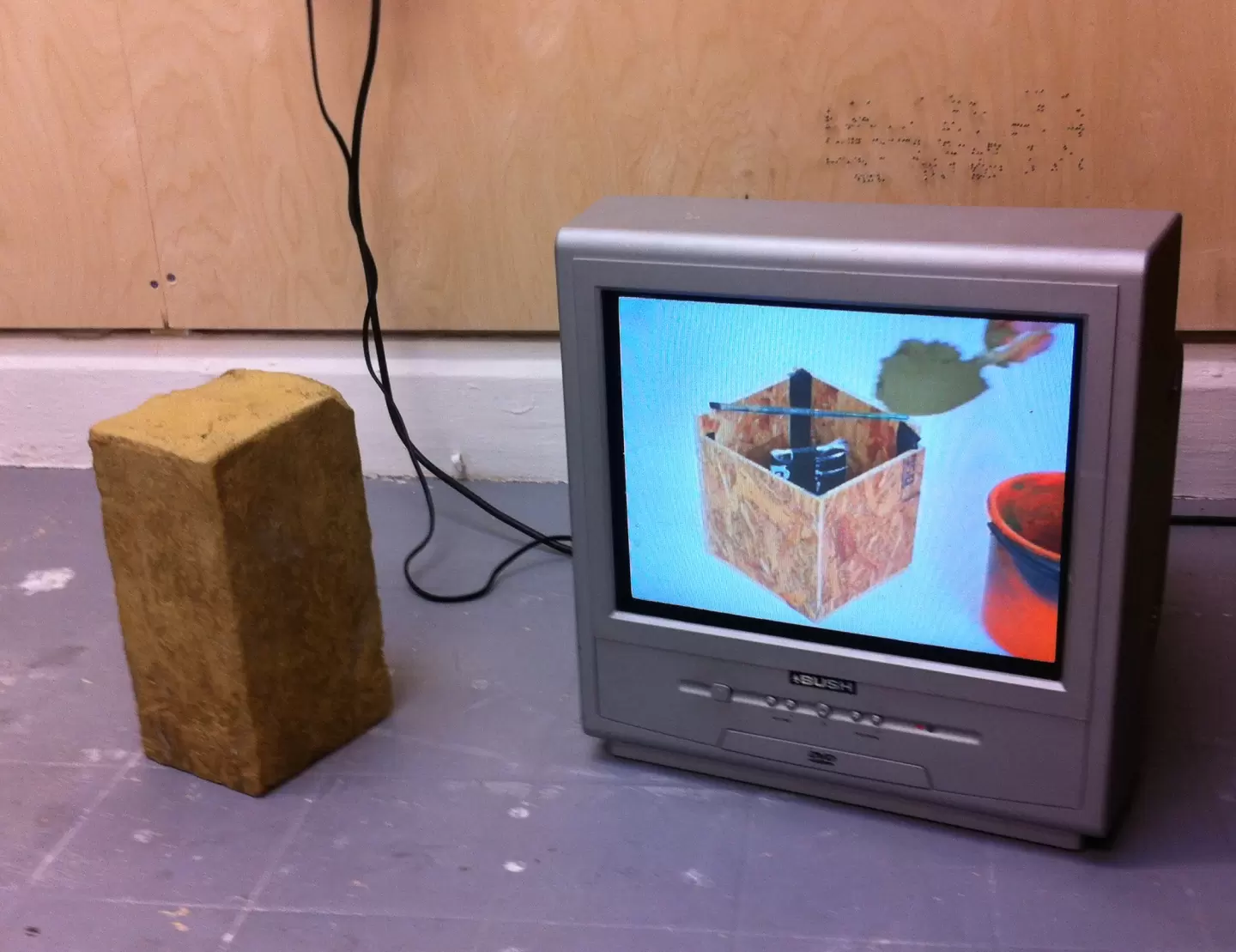

Preserving an object that cannot be used for its purpose is quite common for archival or museum practices.

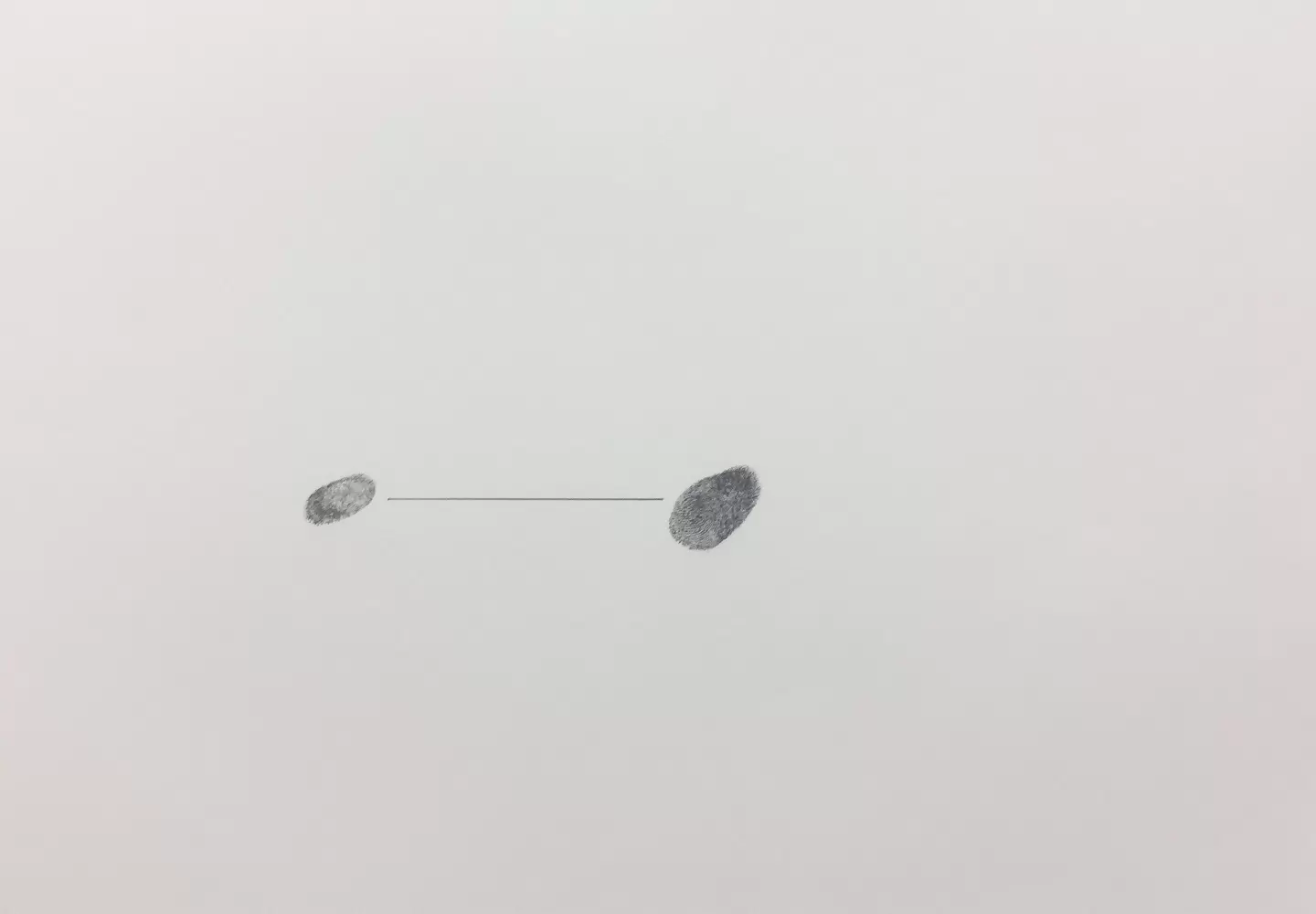

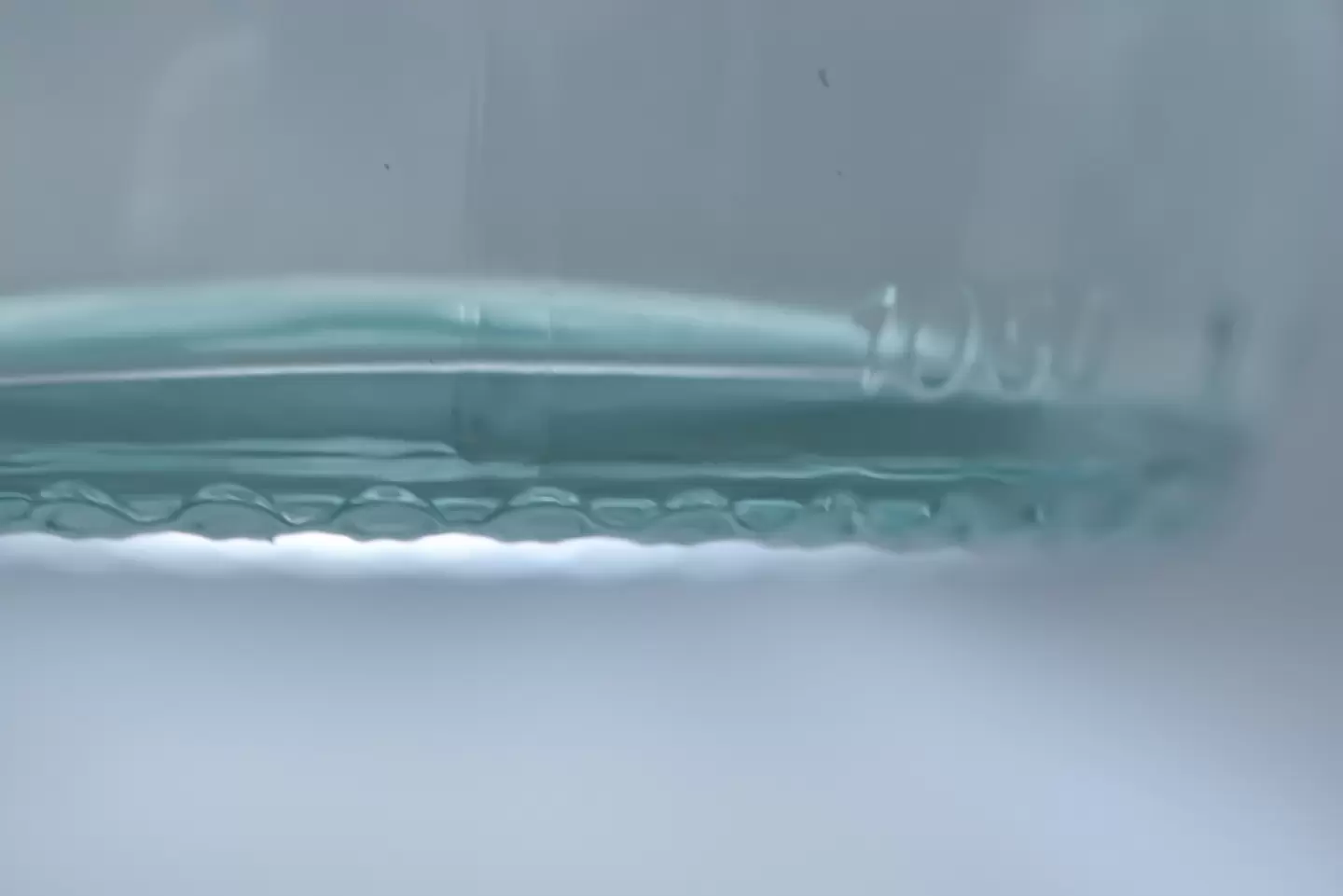

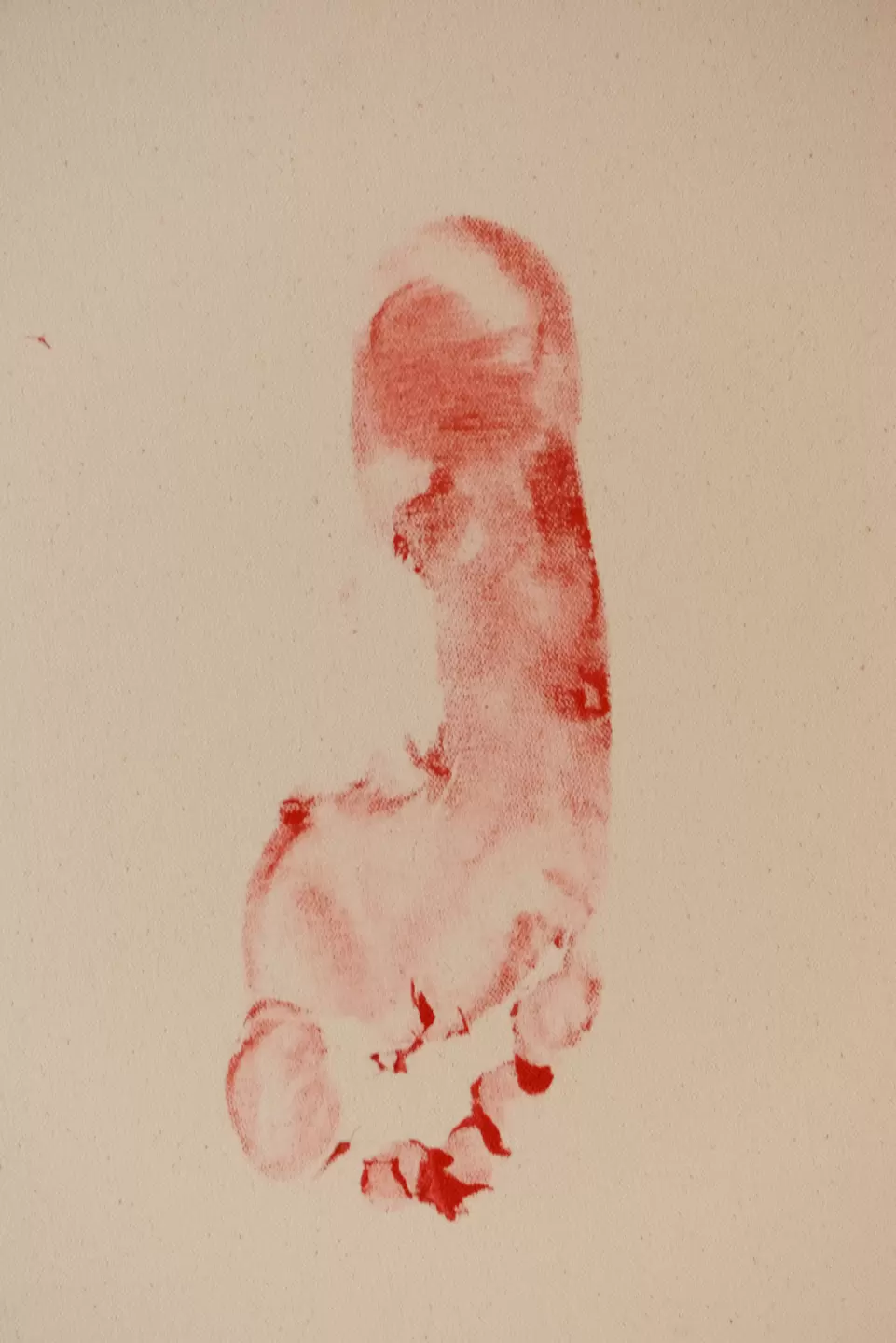

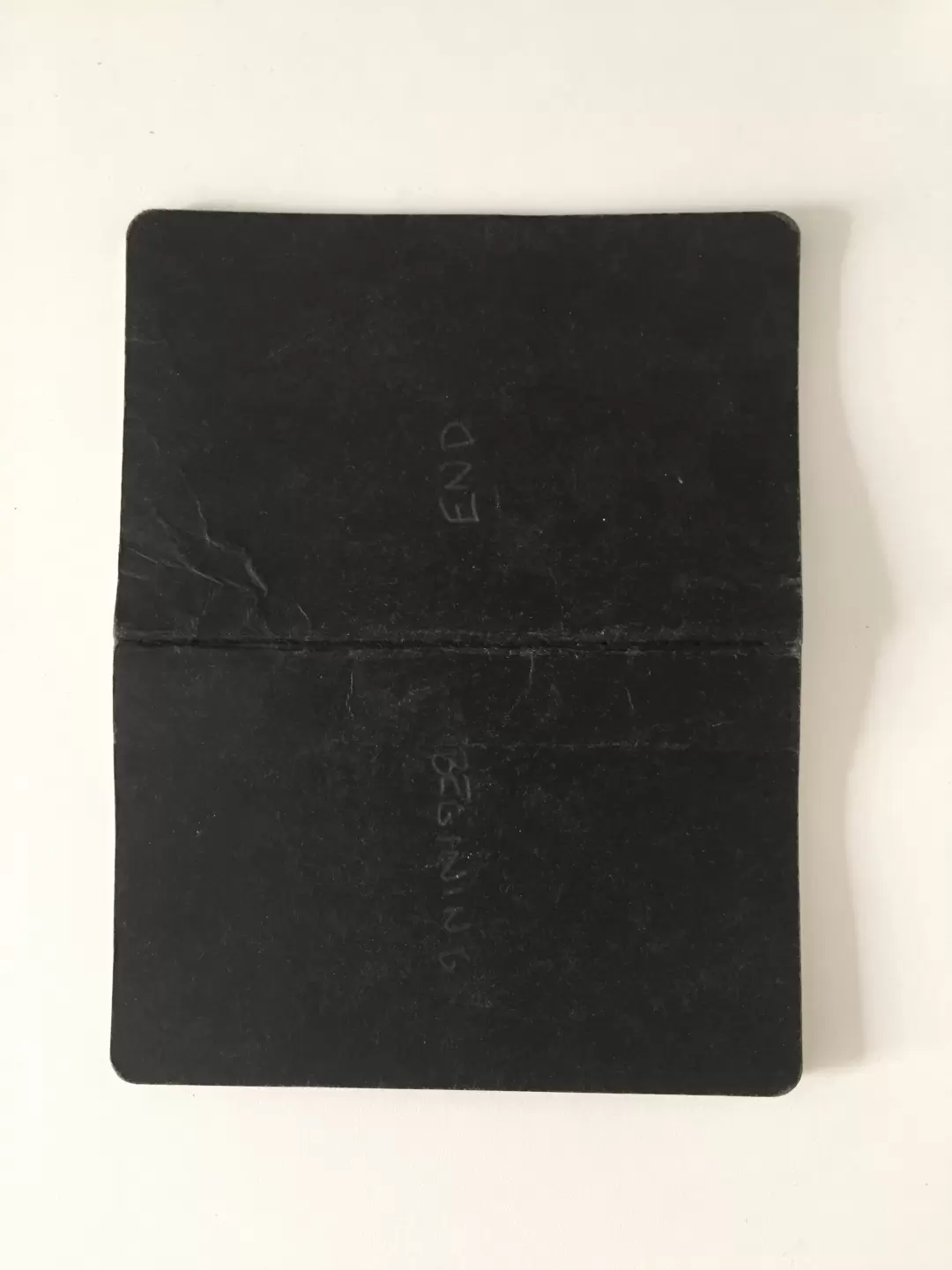

The first ever phonographic recording was made with ink. The sound was marked onto a sheet of paper by a vibrating needle; it was in some sense more of a visual representation of the sound than a phonograph recording, as it could not be reproduced. Wax cylinders embed the grooves visible to the eye in a physical transcription of the recording onto the wax surface. The sounds carved onto an object offer a productive metaphor for the traces events may leave, of their conservation and their transformation into something else.

From a technical point of view, phonographic recording is the most direct way to transfer a sound onto a ‘physical support’ and ensures that the sound is reproducible. This method to record sound has very few obstacles between the actual sound and its physical marking on the surface of the cylinder. The recording is the result of the needle scratching across the wax surface that aims to produce the fewest possible interferences and mediation between the situation and its material embodiment.

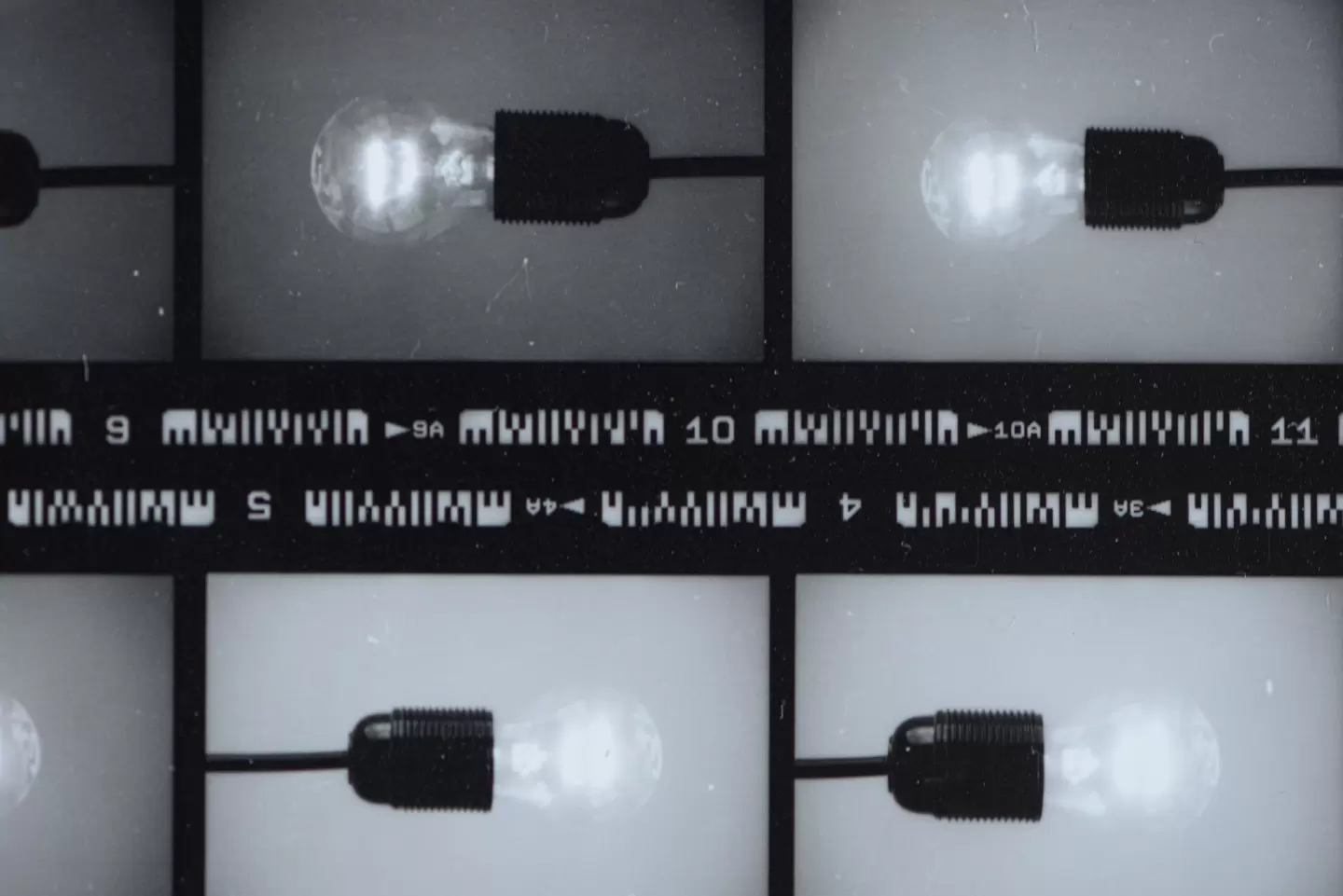

The big difference between analog and digital is that analog recording engraves the moment, while digital imitates it. Digital recording and digital reproduction is an imitation of an event that happened; the phonographic engraving is not an imitation because the analog recording, by precisely using that sound wave , impresses the event onto a surface and thus captures a moment with all the inaccuracies and errors of that specific moment. The digital – instead by imitating – removes everything that is considered error or inaccuracy. Phonograph recording is a momentum.

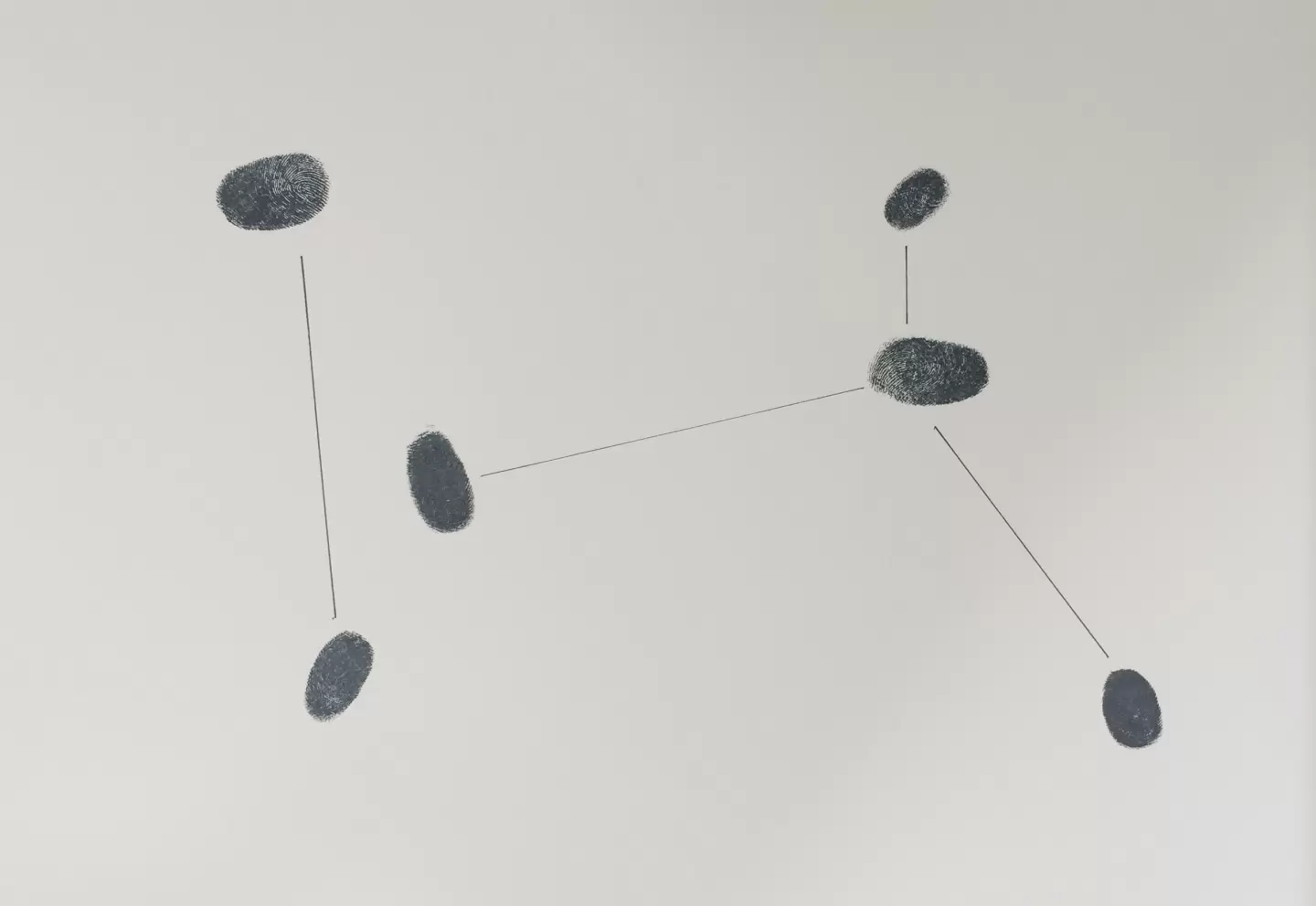

The sound that we hear on a wax cylinder has strong background noises that can be understood as signals that mark the metaphorical distance between the listener and the time-space where the recording was produced. These noises of the mechanical recording are both part of the event that was recorded and the moment of listening.

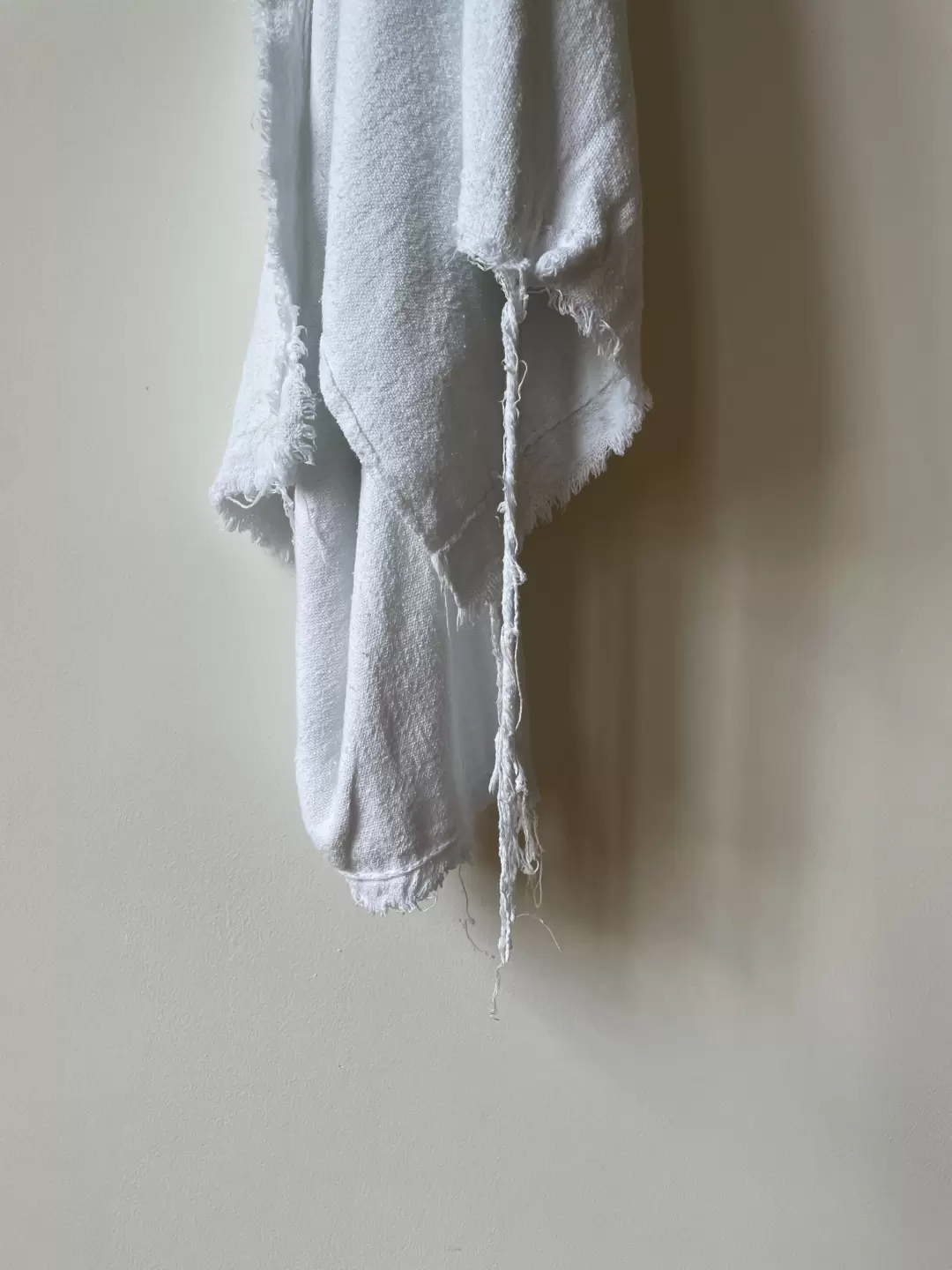

The physicality of the sound reproduced on the wax cylinder is also embodied in its tendency to disappear from the surface if listened to too many times. In fact, the quality and the survival of this object depends precisely on how much it is used: the more you replay it, the more it frays. In this sense, listening to the ephemeral material of the cylinder is an excellent metaphor for the moment that is moving away. The more you listen to it, the more that moment becomes vaguer and less decisive: disturbances, inaccuracies and noises take over. The digital instead idealizes an event in a ‘perfect’ form that does not change over time.

Phonographic recording signaled the first moment in history when humans were able to listen to an event whose present had already passed through exclusively technical mediation. This relationship and perception of sound events has shaped the sonic perception of the past: a scratched, disturbed sound. A phonographic recording, photograph or manuscript are objects that tend to ‘vanish’ over time and create distance between the listener-viewer and the source event.

Throughout European history and culture, archiving has been made equal to the possession of a physical object and the storage of that object somewhere (i.e. in a museum or state archive). This condition is characteristic of the West’s material approach to culture and knowledge that orders a physical proof of existence. Such an approach is diametrically opposed to that of so-called oral cultures, of those not based on written or material matter for transmitting and conserving knowledge. This epistemic divide is crucial for the re-thinking and re-imagining of archives. Should the immaterial and intangible be stored? How and where should it be embodied?

What else if not a wax cylinder?

Edi Danartono, Ollie George, Ekaterina Golovko

14.08.2021